There are certain things expected of a third son. That one will not put oneself forward, that one will join the army, or the church, or the bar. That one will not, in an attempt to inherit and whatever the provocation, murder one’s elder brothers and that one will, if at all possible in the circumstances of being a third son, marry well. Hard and Fast from Speak Its Name.

Erastes is the author of the gay regency Standish and her novella Hard and Fast appears in the Linden Bay Romance anthology Speak Its Name with Lee Rowan’s Gentleman’s Gentleman (Victorian) and Charlie Cochrane’s Aftermath. Her second novel, Transgressions (English Civil War) has been sold to a mainstream publisher and will be out Spring 09.

To be entered into a drawing to win a copy of Speak Its Name, join in the discussion today.

Welcome to the Riskies! What does your name Erastes mean and why do you write under a pseudonym?

Erastes is a Greek word for a mature man who took on as a pupil/paramour a younger man (eromenos) in ancient Greek society. It was a relationship which was considered noble and moral. The older male was both the lover and the teacher of the younger male. He taught him the principles of physical and mental fitness, as well as soldiery and good citizenship. Sex was seen mainly as a way of cementing an emotional bond between teacher and student, as well as a way of expressing admiration for the youth’s physical beauty.

Erastes is a Greek word for a mature man who took on as a pupil/paramour a younger man (eromenos) in ancient Greek society. It was a relationship which was considered noble and moral. The older male was both the lover and the teacher of the younger male. He taught him the principles of physical and mental fitness, as well as soldiery and good citizenship. Sex was seen mainly as a way of cementing an emotional bond between teacher and student, as well as a way of expressing admiration for the youth’s physical beauty.

I picked the name because I felt that – as a writer of gay historical fiction – it would sum up exactly what I was writing about. I picked a penname because I was advised that gay men wouldn’t read gay romance written by a woman. Whilst there are a very few exceptions, I’m very happy to say that this isn’t true and that I get at least 50 percent of fanmail from gay men.

What do you love/hate about the Regency?

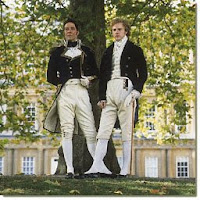

It was a time of sweeping change – Britain moved from constant war to peace, mechanisation was coming – it must have been a very exciting place to live (if you had the money to enjoy it and weren’t on the breadline!) I love the fashions, the way that men were still decorative, possibly the last time that they were so encouraged to wear frills and huge exaggerated collars and cuffs, fobs and seals and doing things to their hair that wouldn’t look out of place in today’s gel-mad society.

It was a time of sweeping change – Britain moved from constant war to peace, mechanisation was coming – it must have been a very exciting place to live (if you had the money to enjoy it and weren’t on the breadline!) I love the fashions, the way that men were still decorative, possibly the last time that they were so encouraged to wear frills and huge exaggerated collars and cuffs, fobs and seals and doing things to their hair that wouldn’t look out of place in today’s gel-mad society.

It was also an era where homosexual men continued to band together; something which had become common in the previous century in Molly Houses. The punishments for sodomy – whilst still lethal with sufficient proof – had become a little more lenient. (If you consider six months in Newgate lenient!) This isn’t something I love, but rather what makes the era fascinating from the perspective of a gay historical author.

It was also an era where homosexual men continued to band together; something which had become common in the previous century in Molly Houses. The punishments for sodomy – whilst still lethal with sufficient proof – had become a little more lenient. (If you consider six months in Newgate lenient!) This isn’t something I love, but rather what makes the era fascinating from the perspective of a gay historical author.

There was so much going on, too. The Thames froze over and the last great frost fair was in 1814 (which is what I’m writing about now) – exploration was going on all over the world and England was carving out a mighty Empire for itself. There are so many opportunities for stories, not all confined to White’s and Almack’s.

Why is the Regency a good setting for male-male romance? What research did you do/what sources do you rely on?

It’s a wonderful era because the sexes were still pretty much segregated. Men weren’t expected to spend time at home with their families and were together in clubs, in their estates, lounging on the edge of the dance floor, strolling arm in arm in Bath, or at war together in the company of many other men.

It’s a wonderful era because the sexes were still pretty much segregated. Men weren’t expected to spend time at home with their families and were together in clubs, in their estates, lounging on the edge of the dance floor, strolling arm in arm in Bath, or at war together in the company of many other men.

When one writes a heterosexual Regency one has to consider the reputation of one’s heroine. She can’t exactly leap easily into a closeted carriage with him, can’t walk alone with him in the moonlight, and even riding around in his carriage alone might be enough to ruin her, but it’s different for men. It gives a writer much more scope for two men to realise their attraction to each other because they are able to spend time in each other’s company without anyone raising an eyebrow.

However, getting them “together” in a more intimate way takes a bit more effort on behalf of the writer!

Why do you think women are so fascinated by male-male erotic romance?

I think that in the main, it’s perfectly normal. Obviously there are some who will find it not to their taste, but if one appreciates the male form, then two males has to be better. After all, what is most men’s fantasy?

I think that in the main, it’s perfectly normal. Obviously there are some who will find it not to their taste, but if one appreciates the male form, then two males has to be better. After all, what is most men’s fantasy?

On a more serious note, though, I think many people are drawn to it because a male/male relationship is a fascinating thing and outside most females’ experience. There’s a definite powerplay which is (in is my opinion) so much fun to play with. No slight female form which can be easily overpowered, no forcing of the man on the woman. Two males who can be equal in rank and stature and neither of them are willing to back down to the other. It’s fun to play with this too. In Hard and Fast Geoffrey is tall and broad, has been in the military for most of his life but – other than his eloquence of the first person narration – he’s almost incapable of voicing his thoughts and opinions, not to his father, his intended wife – or the man who he gradually falls in love with, Adam. Adam on the other hand is physically handicapped with a clubfoot, but this doesn’t make him weak. He’s acerbic and runs verbal rings round poor Geoffrey who, for a large portion of the book, wants to do nothing more than thump him. I don’t think you can show this aggression with heterosexual romance, not without people complaining.

One man unable to express his feelings is fine, but to have two of them? It is a writer’s dream and the opportunity for misunderstandings, sleight of hand and a painful progress to a happy ending (which is a difficulty all of its own) is all grist to a gay Regency writer’s mill!

When you have two men in a rigid society who want to express their feelings for each other the UST (unresolved sexual tension) goes through the roof. It’s the equivalent of the heroine’s hand being pressed by her suitor and that’s enough to sustain her until the next time she sees him. With male/male romance you can crank up the UST to the nth level with straining breeches, interrupted and dangerous liaisons and then finally when you let it rip you have all that delicious male anatomy to describe. Because no self-respecting Regency hero will be unattractive!

When you have two men in a rigid society who want to express their feelings for each other the UST (unresolved sexual tension) goes through the roof. It’s the equivalent of the heroine’s hand being pressed by her suitor and that’s enough to sustain her until the next time she sees him. With male/male romance you can crank up the UST to the nth level with straining breeches, interrupted and dangerous liaisons and then finally when you let it rip you have all that delicious male anatomy to describe. Because no self-respecting Regency hero will be unattractive!

Sex too can be a lot more aggressive with two men. It doesn’t have to be, but some of the most romantic scenes in gay historicals that I’ve read have actually been written by men.

Whose writing has influenced you?

Austen without a doubt, and that’s a very boring answer I know but I immerse myself in the contemporarily written novels to get a feeling for the language and the manners. As soon as I read Northanger Abbey I knew that I had to track down Otranto, Udolpho and the others. (Some of them are frankly awful) but they really help to immerse one in the time. I want to try and transport my reader if I can, not to be reading a book about a time, but rather to be reading a book written in the era. Not going to be possible I know, but I try.

Austen without a doubt, and that’s a very boring answer I know but I immerse myself in the contemporarily written novels to get a feeling for the language and the manners. As soon as I read Northanger Abbey I knew that I had to track down Otranto, Udolpho and the others. (Some of them are frankly awful) but they really help to immerse one in the time. I want to try and transport my reader if I can, not to be reading a book about a time, but rather to be reading a book written in the era. Not going to be possible I know, but I try.

Dickens, Tolstoy, Saki… I’m afraid I’m a bit of a fossil all around, and one young wag whilst looking at my bookshelves once said “have you anything from, you know – even last century?” A calumny, as I do have many modern books, but they do tend to be historical fiction! Modern influences without a doubt are Mary Renault whose The Charioteer remains a beacon and an unattainable perfection that I could never reach, and the amazingly brilliant At Swim Two Boys by Jamie O’Neill which is everything a gay romance should be. Funny, tragic, social commentary, wrapped together with some of the best characterisations I’ve ever read.

Usually we ask guests what makes their work risky (our standard question)–what do you see in your writing that pushes the envelope?

I’ve probably covered this a little but just writing gay historical fiction in itself is doing that; there are so very few of us writing it in this day and age that it’s scary. (Take a look at the finite resource of gay historical fiction here on my website.) I don’t just want to write gay erotica – there are many other people doing that from every sexual persuasion – or modern men in fancy dress – I want to try and imagine how it really might have been for gay men, from the Regency, from the English Civil War, from Shakespeare’s time and attempt to extrapolate how their lives were and what hoops they had to jump through to find love and sex in times when it was dangerous and often lethal to do so.

I’ve probably covered this a little but just writing gay historical fiction in itself is doing that; there are so very few of us writing it in this day and age that it’s scary. (Take a look at the finite resource of gay historical fiction here on my website.) I don’t just want to write gay erotica – there are many other people doing that from every sexual persuasion – or modern men in fancy dress – I want to try and imagine how it really might have been for gay men, from the Regency, from the English Civil War, from Shakespeare’s time and attempt to extrapolate how their lives were and what hoops they had to jump through to find love and sex in times when it was dangerous and often lethal to do so.

I don’t want to preach or teach history – but readers have said “Hey! I didn’t know X fact” or whatever else they’d learned from my books and if I can open people’s eyes to the past, it’s got to help in the present, I hope.

When my daughters were young, I read to them all the time. This summer, I had the joy of doing it again.

When my daughters were young, I read to them all the time. This summer, I had the joy of doing it again.