Every year, June 18 always brings with it thoughts of the battle of Waterloo, an epic battle that claimed tremendous losses for its time but ultimately altered the course of world history. But I also always think of the huge commemoration of the battle that occurred two years later in London, when the latest among the new River Thames bridges was opened with much pomp and fanfare. (The Vauxhall Bridge, the first cast iron bridge across the river, opened the previous year.)

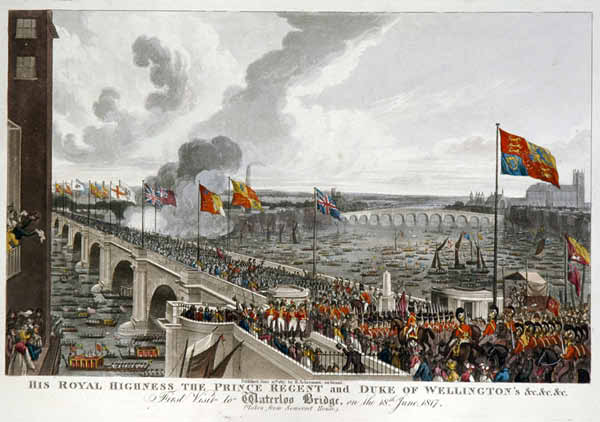

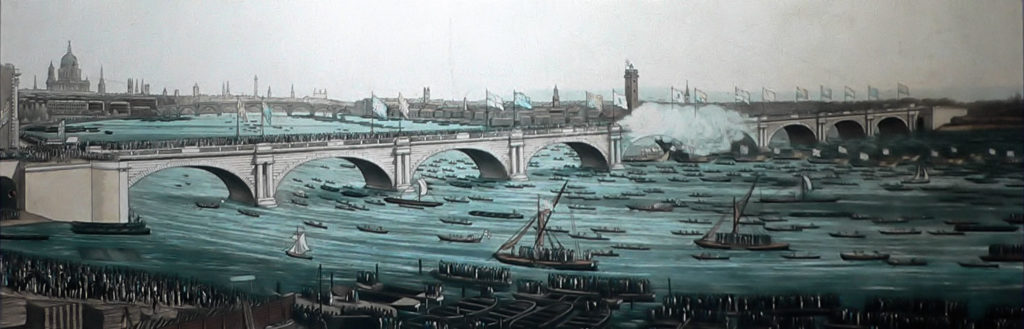

Many artists attempted to capture the scene, and a look at their pictures shows why: the river is literally filled with every conceivable type of watercraft, and people crowd every available space along the riverfront that could afford a view of the proceedings. All of that, in fact, seems more of interest than the actual ceremonial proceedings upon the bridge itself. The Ackermann illustration above (public domain) is my favorite, because it shows the view from Somerset House, looking the opposite way from most of the other, more distant views, including the famous seven-foot-long one by John Constable in the Tate Museum collection, completed in 1832 (below, cc by public domain, Wikimedia Commons).

In the last of my old Signet/NAL Regencies, The Rake’s Mistake (2002), my hero and heroine attend this festive occasion in his small sailboat, the Ariadne.

“By noon the banks of the Thames beyond Westminster Bridge were crowded with spectators on both sides of the river, in the gardens, on the rooftops, and in stands that had been constructed on wharves and in many of the yards. Huge barges that normally carried corn or coal were loaded this one day with human curiosity instead. A flotilla of sailboats similar to the Ariadne milled about in mid-river, weaving in and out of an even larger assemblage of rowed vessels—excursion boats, private barges, watermen’s wherries and the like. Many of these vessels carried flags that snapped and fluttered smartly in the breeze. Buildings and even several church steeples were similarly adorned, while eighteen standards flew upon the bridge itself. Ramsdale furled the sail and anchored the Ariadne close enough so that as he and Daphne delved into the contents of their picnic hamper, they could listen to the Footguards band that was among the military detachments stationed on the bridge.”

The river is actually an important character in that story, and I have blogged about the River Thames here before (July 2016). (I still haven’t re-issued that book as I feel it needs extensive revisions, and the new Little Macclow stories set in Derbyshire are taking up my time and brain! It is currently out of print.)

Enterprising people with access to the riverfront or places overlooking it were selling viewing spots for weeks in advance of the actual bridge opening. Here is an example of a newspaper notice from June 11, a week before the event:

“OPENING OF WATERLOO BRIDGE June 11, 1817 Apartments and places commanding a complete front view of the intended Royal procession on Wednesday next, in Commemoration of the battle of Waterloo, may be had by early application to Mr. Stevenson, No 41, Drury Lane, near Long-Acre.”

Mr. Stevenson was very likely acting as agent for a number of different persons who were too genteel to be directly involved or, in the case of businesses, too busy to want to manage the details of these one-time side-line transactions.

Not everyone was in favor of naming the bridge after a battle that had occurred on continental soil. Some critics felt the name was out of keeping with all of London’s other bridges, since all of the others referenced something to do with London. The bridge, when originally proposed in 1809, was intended to be called the Strand Bridge. Work on it was begun in 1811. It was only in 1816 that a Parliamentary Act was passed to change the name to Waterloo Bridge as “a lasting Record of the brilliant and decisive Victory achieved by His Majesty’s Forces in conjunction with those of His Allies, on the Eighteenth Day of June One thousand eight hundred and fifteen.”

What do you think? Was naming a bridge for the battle an appropriate commemoration, even as an anomaly? Or were the Regent and the other powers behind the bridge project simply too carried away by their enthusiasm for the important victory? Would you have liked to attend the grand opening celebration?

According to The Survey of London, the bridge cost £618,000 (c. $58.5 million in today’s U.S. currency or £37.1 million UK) and the total cost of the bridge and its approaches was £937,391 11s 6d. (c. $88.8 million or £56.1 million UK). It began as a “penny toll” bridge, but as the Survey authors point out, “As a commercial speculation the undertaking was far from being a success since, in order to avoid payment of tolls, many people who would otherwise have used the bridge made a detour to cross the river by Blackfriars or Westminster Bridges, which were free.” The toll operation ceased in 1877.

Sadly, the lack of success as a toll bridge led to a more tragic form of success as a prime site for suicides—so especially sad given the high hopes and celebration when the bridge opened. The lack of traffic compared to other London bridges meant anyone intent on suicide was less likely to be seen or stopped before they could carry out their final act. Newspapers carried many accounts of poor souls who ended their days by jumping from Waterloo Bridge. There were enough to inspire poets and artists of the mid-Victorian era, and a new nickname arose from Thomas Hood’s 1844 poem “The Bridge of Sighs”, about a homeless woman who jumped from the bridge.

The bridge began to deteriorate by the end of the century, and by the 1930’s debate was whether to attempt to repair it or replace it altogether. The decision was made to replace it, and the work carried out during the war years of the early 1940’s, mostly by women. This gave a new nickname to the replacement Waterloo Bridge opened in 1942 and completed in 1945: the “Ladies Bridge” in view of their labors to build it and despite the opening day remarks that credited “the men” who had supposedly created it.