Do you think overblown “holiday light displays” (or the desire to ride around viewing them) are a phenomenon of our modern age? Step back into the Regency with me for a moment.

The trail of research we authors do as we work on our stories often leads into interesting nooks and crannies, if not right down infamous “rabbit holes.” Researching the events of April 1814 for my current wip (reading the newspapers of the time, one of my favorite ways to research) led me to chase down information about the celebratory “illuminations” that were hurriedly put up once the news of the Allies’ victory in France and the abdication of Napoleon became officially announced in London. While the references to them in my wip are just casual conversation, I wanted to know what, exactly, my characters had seen!

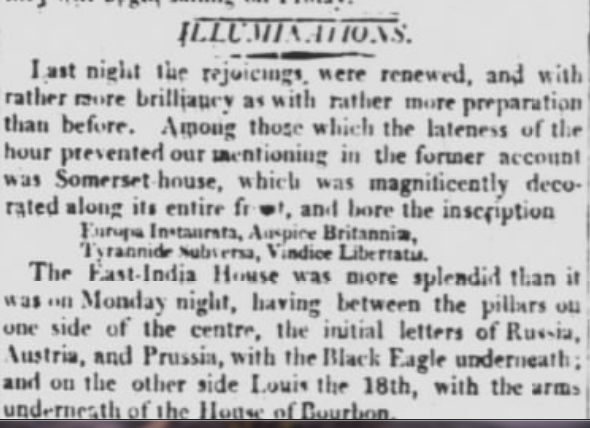

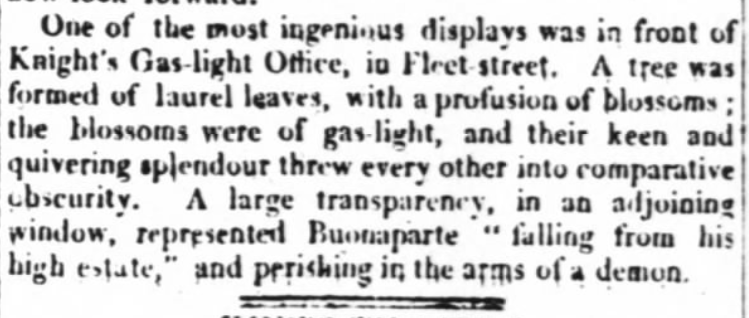

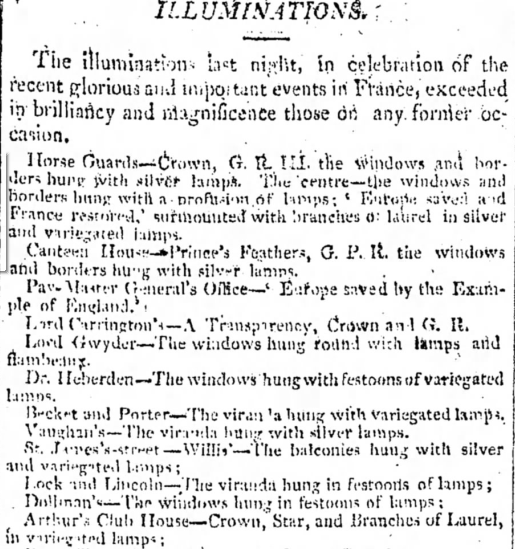

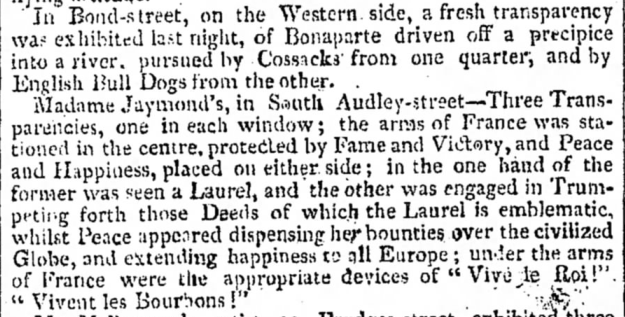

The news of peace in Europe broke over the 9th-10th, which was Easter weekend of that year. Descriptions of many of the more prominent displays are given in both The Times and The Morning Chronicle, April 11-13, which is just when my story begins. Many of the displays are described as “transparencies” –colorful paper or cloth images which were illuminated by placing a light source behind them. The first two excerpts are from The Times, while the third is from the Morning Chronicle (and went on for two full-page columns on that day):

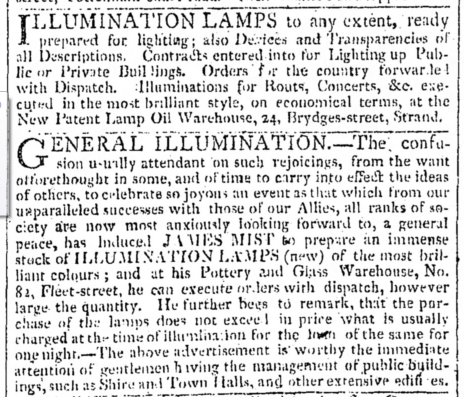

Advertisements for purchasing ready-made “transparent” illuminations and lighting can also be found in these papers. They tell us so much: glass and ceramic lamps in colors could be purchased or simply rented for a single night’s display, and transparencies were made ready very quickly (kind of like commemorative T-shirts are today when breaking news happens)! You could hire someone to design and come put up your display (just as some people do for the holidays today). And we see these displays were also popular for special events, not just national celebrations of major news events, and not just in the city.

Even though Jane Austen describes illuminations (presumably home-made transparencies simply for decoration) in Mansfield Park and also refers to some in her letters, I hadn’t paid attention to this aspect of Regency celebrations until now. I think the evolution of the form seems a natural one, given the ancient interest in the art of stained glass. People have been intrigued by the play of light shining through color as a decorative art for a long time! Transparencies were a way to achieve a similar effect on a temporary basis and at a fraction of the cost.

Of course, one of the wonders of Internet research these days is the bountiful yield of posts that have been written by others also fascinated with the same subjects. But what also interested me was the perfect illustration of how the wealth of material on the Internet continues to expand over time.

Kathryn Kane’s blogpost (from 2012) is fabulous in describing the process of how transparencies were made, including the fashion for making them from prints or original artwork on a small scale by ladies at home. She also leads into this with some background history on illumination. (I wrote a post about street lighting myself, here). The word “illumination” seems to have evolved to refer both to the displaying of lights themselves as part of a celebration and also the display of so-called “transparent” art set in front of such displays of lights. But at the time of Kathryn’s blog, no one had uncovered, or at least posted, any pictures to illustrate what she was talking about.

By 2016 when Shannon Selin wrote an excellent post in this topic (here), she had discovered a Gilroy cartoon at the Yale Center for British Art, showing a decidedly political use of transparency art, not quite what we’re talking about here, but still giving an idea of the form. The pictures are mounted in a wooden frame, placed in front of the light.

Selin, author of the alternate history novel Napoleon in America, offers more details than Kane about the “how-to” books and designs that were published for the home craftsperson. She says Rudolph Ackermann “published 109 transparent etchings between 1796 and 1802,” and also cites a book, Instructions for Painting Transparencies (1799). She writes: “British engraver and publisher Edward Orme encouraged the fad for transparencies in both England and France with his bilingual manual, An Essay on Transparent Prints and on Transparencies in General (1807).” She includes a description paraphrased from Orme on how to turn an etching or engraving into a transparency. She writes: “This involved painting large areas of color on the back of the print (corresponding with the outlines of the illustration), and then adding varnish to specific areas to give the paper a see-through effect when held up to light. Scraping or cutting away small sections of the surface was another way to enhance the transparency.”

Finally, I found a blogpost from 2018 that shares the writer’s discoveries while delving into the Georgian Papers collection in the British Royal Archives under a fellowship grant. The illustrations she found are delightful and I direct you to Cassandra Good’s post (here) to see for yourselves, because copyright permissions don’t allow me to share them in this post. I hope you will particularly study the 1763 design by architect Robert Adam for what he called a “transparent illumination” to celebrate the King’s birthday. It appears to show huge transparencies erected on portions of the building, which would have been quite spectacular to see, especially lit from behind. These are a far cry from the small, window-pane sized illuminations described in Kathryn Kane’s post and most likely would have been painted on fabric rather than made of paper.

My conclusion is that “transparent illuminations” (to distinguish them from the illuminations made only with candles, lamps or other light sources) could vary in size from the spectacular displays mounted on buildings to the small displays in household windows, and the elaborateness of the design as well as the size and artistry would reflect on the financial resources and inclination of the displayer. This helps me to put some of those newspaper descriptions into perspective.

I think the social ramifications are interesting to speculate about. If you purchased ready-made illuminations destined for your front windows, would you be worried your neighbor might have purchased the same one(s)? Would families have been conscripted to spend their evening hours in those same front rooms to keep an eye on the illuminations for safety reasons? Lamps or lanterns might supply some degree of safety, but open candle flames were always a hazard, then as now, and paper (even the linen-rag paper of the Regency) soaked in varnish or oil would have been very flammable.

Was there also a risk that drunken revelers in the streets might take offense at the chosen designs on display? There are early accounts of destruction and broken windows when illuminations were done in support of partisan ideas or unpopular causes, or were just deemed “inadequate” by fickle mobs. And not just in England. Illuminations were part of special celebrations in America and France in this period as well.

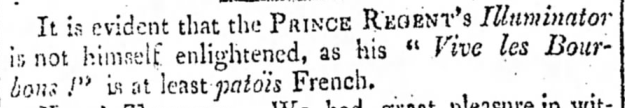

Certainly at least the efforts by the high and mighty were just as subject to censure as they are today. The Morning Chronicle was quick to point out an error in the illuminations mounted by the Prince Regent in April, 1814. The defeat of Napoleon was celebrated as a restoration of the House of Bourbon, the French monarchy (even though in a new “constitutional” form), and many illuminations featured congratulatory slogans in French. The Chronicle greeted the elaborate design shown by the Regent with the snidely oblique criticism:

I suspect that the political leanings of the Morning Chronicle might have been showing a bit, but OTOH maybe it only proves that “you just can’t get good help” even if you’re the Prince Regent. Or at least that the “grammar police” have been around for a really long time!

What do you think? Did you know about these elaborate displays of lights and art during the Regency? When the holidays roll around again this year and you see the displays on people’s homes, will you think about the historical roots behind the tradition? Please leave me a note in the comments! And thanks so much for reading.