The English count the 12 days of Christmas as starting on Christmas Day itself, so Christmastide, or the Twelve Days of Christmas culminate tonight with Twelfth Night, ushering in the Christian season of Epiphany. Which customs did people follow to celebrate this during the Regency?

The more research you do to answer this question, the less of an answer you will find, for sources contradict each other and assumptions are made where information is lacking. Twelfth Night itself is ages old, and in earlier times eclipsed Christmas as a major holiday. The rituals and customs associated with it, and with the twelve days, are myriad.

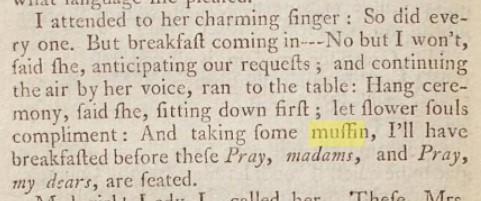

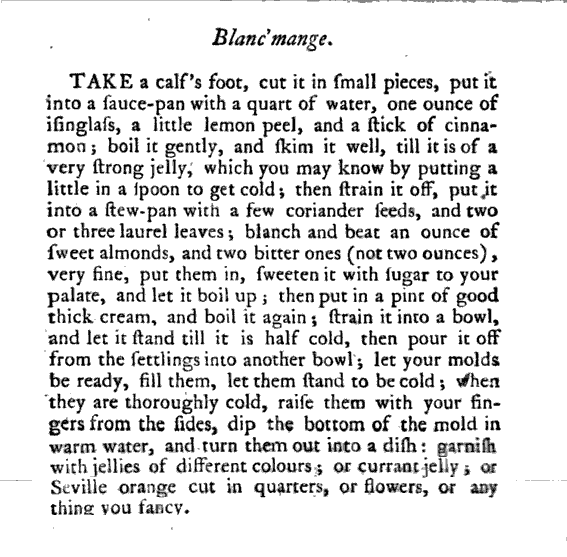

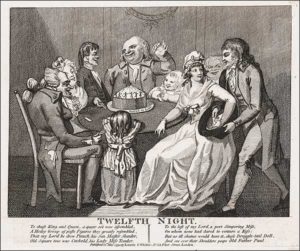

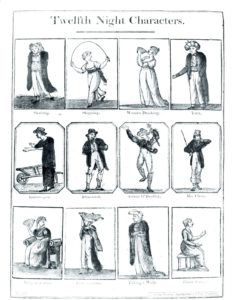

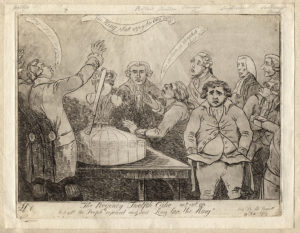

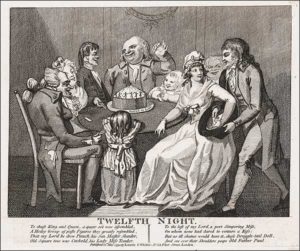

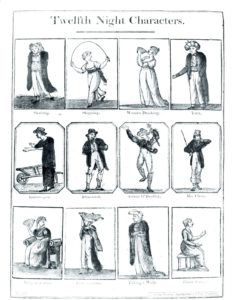

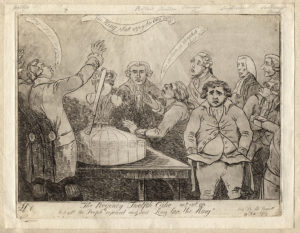

Did people exchange gifts? On Christmas? On Twelfth Night? All through the Twelve Days? Evidence (newspaper ads for instance, and lists of gifts received kept by individuals) would suggest “all of the above”, despite some accounts that say the practice had faded out by late in the Regency. Did they still dress up as “12th Night characters” to entertain each other at parties? Jane Austen mentions this. Still celebrate with 12th Night cake, or choose a King and Queen of the Bean? Perhaps at least in the early Regency, and of course it depends on class, location, and other variables.

“…these venerable customs are becoming every year less common : the sending of presents also, from friends in the country to friends in the town at this once cheerful season, is, in a great measure obsolete: ” nothing is to be had for nothing” now ; and without the customary bribe of a barrel of oysters, or a fish, we may look in vain for arrivals by the York Fly, or the Norwich Expedition….” –Kaleidescope of January 1822.

Elsewhere in his article the writer says: “During the period which elapsed, between 1775 and the close of the 18th century, the periodical observance of old customs, festivals, and holydays, was much more attended to than at present. The recurrence of the time hououred festival of Christmas, was commemorated in Liverpool, to an extent much beyond what is now the usage, though in a degree inferior to the manner in which it was observed in the age which was gone by.”

Were the old customs celebrated in Washington Irving’s fictionalized account of an English Christmas in “Old Christmas” from his larger work, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.(published serially 1819-20) truly inaccurate, as claimed by the same writer?? His complaint about Irving’s work: “It is true that the Sketch Book is merely a work of imagination and not of history, and that it describes Mr. Bracebridge as an eccentric elderly gentleman, who was fond of keeping up or reviving ancient customs and old pastimes, but it is so expressed that a stranger to English habits, on reading it, can scarcely avoid falling into the error of imagining that such a mode of celebration, was observed at Christmas, in some parts of England, at the time when that book was written, or at least, in very modern times. Even if all the ceremonies, sports and observances which are there described, ever were commonly practised at Christmas, in English families, it was in an age long since past, and there is no reason to believe that the mode of observing or celebrating Christmas, described in the Sketch Book, ever occurred in England, within the last hundred years.”

The writer seems to ignore Irving’s own words in the piece itself: “I felt an interest in the scene, also, from the consideration that these fleeting customs were posting fast into oblivion; and that this was, perhaps, the only family in England in which the whole of them were still punctiliously observed.”

My belief, as always, is that –humans being humans– not everyone did the same thing, so what may be true for one area of England, or even one village, or one family, might not be true for another. We also know that, especially in the countryside, memories in England were very long and tradition revered.

This is good news for us as fiction writers. We try to recreate an accurate sense of the time period we set our stories in –otherwise, why choose that period? But at the same time, we have a story to tell. Do we have leeway to bend the facts to serve our story?

I would say no, when the facts are definitely known and established. To me, that just undermines the believability the story needs to create. I’m a firm believer in the importance of research! But when the facts are not so definite, when sources disagree or are vague? When the variable eccentricities of human nature come into play? Then I say, bring it on!

I admit to creating a setting –a backwater village that clings to old traditions –in my yet-unfinished 12 days tale, The Lord of Misrule. Even the predicament of my hero, who is stranded in said village and quite accidentally (perhaps) selected to be the Lord of Misrule, is an anachronism, since for the most part as far as we know that custom of having a Lord of Misrule was abolished in the 17th century (and even that is subject to all sorts of variations, from ruling for 3 months, October-December, to the 12 days of Christmastide, to only ruling on the also abolished Feast of Fools, or only on Twelfth Night itself).

What do you think? Does a lack of solid information give us license to do what we please for the sake of a story? Whatever your opinion on this, I wish you a Happy New Year “and many of them” as one 1805 newspaper encouraged people to say. Happy Twelfth Night, too!