… or at least I hope I will.

And not just any castle, but Castle Sooneck, one of the umpteen (and I mean UMPTEEN!) castles, ruin, and other historic sites along the banks of the river Rhine in the Upper Middle Rhine Valley. A cultural heritage organisation of the area as well as a local newspaper were looking for a “castle-blogger,” somebody to move into Castle Sooneck for six months and blog (in German and English) about life on the banks of the Rhine. The deadline for applications was at midnight on Sunday – and of course, I sent in my application. For how cool would it be to live in a castle?!?!

Well…

Let’s just say it probably won’t be all roses and rainbows: Apparently the view from the castle-blogger’s bedroom will be the (active) stone quarry next door. And down in the valley up to 400 trains a day pass by on one of the major transport routes of Europe.

Add to that that castles tend to be drafty places and that those thick walls don’t make for particularly warm rooms. What the colder season (= anything that’s not summer) can be like in a historic building is rather vividly described by the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire in the chapter about “Cold Houses” in her book Home to Roost:

“A new heating system was installed when we moved in[to Chatsworth] and it works pretty well. Even so, the wind can penetrate huge old window frames which don’t fit exactly. In September we go round with rolls of sticky brown paper to stop the gaps. When the front door is open and people with luggage dawdle, all our part of the house feels the blast so we’ve cut out a small door out of the big one and you have to enter at speed. There are zones of intense cold, seldom visited in winter: the Scupture Gallery, State Rooms and attics, where a closed-season search for forgotten furniture can feel colder than being out of doors.”

I would imagine that it’s probably different in a castle (if anything, it would be worse). But hey, that’s what woolen sweaters, thick socks, and the tea kettle were made for, right? Moreover, the scenery of the Upper Middle Rhine Valley would certainly make up for any minor inconvenience: it is one of the most beautiful areas of Germany – and Regency people were mad for it.

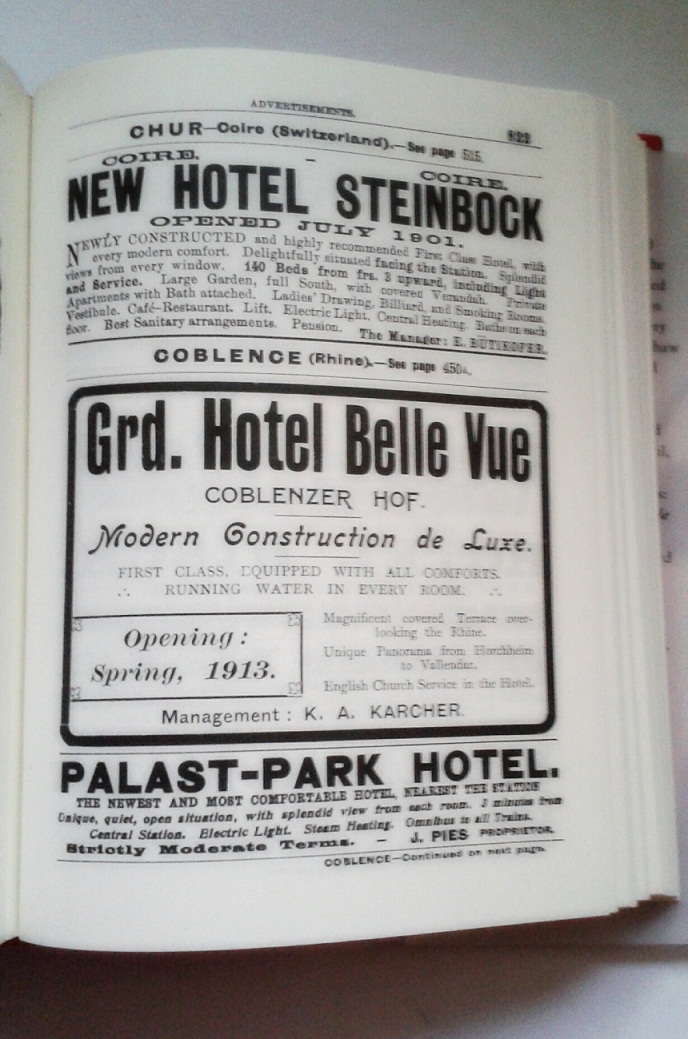

Tourism dwindled down during the Napoleonic Wars, but as soon as Napoleon was safely banished to his island, the British came back to the Rhine in huge numbers, undeterred by either customs stations or the German beds, which, apparently, were on the horrid side if Murray’s Hand-Book for Travellers on the Continent: Northern Germany, 1845 is to be believed:

“One of the first complaints of an Englishman on arriving in Germany will be directed against the beds. It is therefore as well to make him aware beforehand of the full extent of misery to which he will be subjected on this score. A German bed is made only for one: it may be compared to an open wooden box, often hardly wide enough to turn in, and rarely long enough for an Englishman of moderate stature to lie down in.”

No, not even the German beds could deter the British tourists. Happily, they all followed in the footsteps of Childe Harold, often dragging a copy of Byron’s work along on their journey to appreciate more fully the

blending of all beauties; streams and dells,

Fruit, foliage, crag, wood, cornfield, mountain, vine,

And chiefless castles breathing stern farewells

From gray but leafy walls, where Ruin greenly dwells.

The ruins and castles still dwell along the Rhine, and it would be a great thrill indeed to explore (and sketch!!!) them all as the castle-blogger of Sooneck. 🙂

~~~

What about you? Would you like to live in a castle for six months? Or would all the stairs put you off?