Happy Labor Day!

This US federal holiday celebrates the economic and social contributions of the American worker. It was first observed in New York in 1882 and became a federal holiday in 1894. Today it has also become the traditional end of summer and the traditional way to celebrate is to have a picnic.

Of course Labor Day 2020 is like no other. Many of our work force are unemployed or underemployed due to the Covid-19 Pandemic, and many of the employed cannot go into work, but must stay at home. Still others, especially our doctors, nurses, and other health providers, are on the front lines, risking their lives for the rest of us. Still others are protesting in the streets, because it is time to for all men (women and children) to be created equal.

So life is no picnic right now. Many of us are hunkering down in our homes, but others are trying to celebrate this holiday as we used to — with a picnic outdoors.

Today’s picnic, albeit a socially distanced one, is a leisure pastime for ordinary people, a chance to grill hot dogs and play outdoor games, but during the Regency, a picnic was a fancier affair, and the working people of the period may have experienced it much differently than we do today.

In the early nineteenth century, picnicking was a way for the privileged classes to commune with nature, all the while consuming a feast assembled to minimize inconvenience and to enhance the outdoor experience. A beautiful site was selected some distance away. Each guest might have provided a dish to share or the host provided all the food. Entertainments were provided. The idyllic interlude was a pleasurable respite from day to day life.

Except for the servants, for a Regency picnic required a great deal of work.Servants had to prepare, pack, and transport the food, the furniture, the plates, serving dishes, cutlery, and linens. The whole lot would be loaded on wagons but the wagons often could not reach the exact site of the picnic, so that the food, furniture, etc. would all have to be carried the rest of the way by servants, who would then have to set up everything, serve the food, and attend to the guests in any way they required. When the picnic was over, the servants had to clean up, repack everything, and carry it back.

It wasn’t until later in the Victorian period, with the rise of the middle class and the ready train transportation that picnics became a less exclusive leisure activity. So on this day, while we celebrate our very unique Labor day, let’s also remember the labor that used to go into a picnic. And let’s remember that times do get better!

(an earlier version of this blog post appeared on September 5, 2011)

Do you ever catch yourself wishing you had a cook and a housekeeper? How about a lady’s maid to do your hair, or a footman you could send to the store? My schedule imploded this week thanks to a big surprise project at work, and once again I caught myself wishing for that kind of extra help.

Do you ever catch yourself wishing you had a cook and a housekeeper? How about a lady’s maid to do your hair, or a footman you could send to the store? My schedule imploded this week thanks to a big surprise project at work, and once again I caught myself wishing for that kind of extra help.

My family has already pointed out to me that clones wouldn’t do. They would be just like me, and therefore likely to enthusiastically embrace new projects, rather than merely help complete the existing ones, so they would multiply the problem rather than solve it. (sigh)

If you could have whatever servants you wanted, which ones would you choose? Our modern conveniences have made some servant jobs obsolete –scullery maid, for instance. In a large Regency household, the scullery maid washed all the dishes, pots, and pans, not only for the family, but also those used by the other servants, all of whom outranked her. Today the dishwashing machine handles most of that.

I don’t think I need a butler, either, even though in the Regency the butler might reign supreme over all the other servants in a household where there wasn’t a steward over him. The butler managed the wine cellar, looked after the good silver cutlery and plate, and supervised all the male servants in the household under him, especially the footmen who served the family and guests at dinner. He sorted the mail (well, on second thought, that still might be useful to me), and welcomed or turned away the visitors who came to call. (We have few visitors. Could a butler manage my social media?)

The housekeeper was, in many households,  of nearly equal rank with the butler, and often was trusted with keeping accounts and other management duties, which might have been shared with him. It was her job to supervise all the female servants under her, which would have included all the different types of maids (chamber maids, house maids, laundry maids) and sometimes, the cook, although male cooks were preferred in the wealthiest households, and in many homes the cook and housekeeper were equals.

of nearly equal rank with the butler, and often was trusted with keeping accounts and other management duties, which might have been shared with him. It was her job to supervise all the female servants under her, which would have included all the different types of maids (chamber maids, house maids, laundry maids) and sometimes, the cook, although male cooks were preferred in the wealthiest households, and in many homes the cook and housekeeper were equals.

A housekeeper and a couple of maids would be very welcome in my house –for paying the bills, keeping track of supplies, tending to my clothes, and getting rid of the unwanted stuff that accumulates around here! Most especially, for CLEANING. Everything! And a cook would be worth her weight in gold in my household.

Footmen. Well, who wouldn’t want a couple of those? In the Regency, footmen seeking positions often included their height as part of their qualifications. It seems that you wanted your footmen to come in matched sets, and the more handsome, the better! Experience, reliability and character were not enough. Footmen were handy because they could accompany you on errands and carry your packages, open doors, or if visiting, they would go to the door and present or leave your card. They could assist you in and out of you high carriage if you actually needed to get out. They waited on table at meals, and might be charged with answering the door if the butler was busy with other tasks. These days? I would love to send my footman to run my errands –think of all the time that would save!!

I admit I don’t have need for a coachman or a groom, thank you, but a gardener would be heavenly! For a place that has no lawn, our property needs an awful lot of pruning, weeding, and other kinds of yard care.

Of course, having servants meant having enough of the ready to cover the cost. During the Regency, there was a tax to be paid on male servants in addition to their wages, their room and board, and the additional expense of clothing them and providing for incidentals. (A candle to light their room at night? Extravagant!) That was one reason the more modest households often employed only female servants. Females were also paid lower wages, even for similar work. (Hmm, some things take a long time to change.) Servants also had to be paid “board wages” if the employer’s family was not in residence for any length of time.

Of course, having servants meant having enough of the ready to cover the cost. During the Regency, there was a tax to be paid on male servants in addition to their wages, their room and board, and the additional expense of clothing them and providing for incidentals. (A candle to light their room at night? Extravagant!) That was one reason the more modest households often employed only female servants. Females were also paid lower wages, even for similar work. (Hmm, some things take a long time to change.) Servants also had to be paid “board wages” if the employer’s family was not in residence for any length of time.

Even other people’s servants cost you money in the Regency, for tips (called vails) were expected, especially if you were visiting. Do you remember to leave a tip for your chamber maid when you stay at a hotel? Well, the same was expected then when you stayed at someone’s country house, and not only for the maid who tended your room, but any other servant who gave you service, whether it was the butler, the groom, or the host’s valet on loan to help your husband with his attire. (A valet today would probably refuse to work with my husband’s wardrobe!) These costs had to be considered before accepting just any invitation.

Employers not only had to follow the terms of the employment contracts, but they had to observe the strict social pecking order among the servants themselves. Heaven forbid if you asked one servant to perform a task that was the duty of another!

If you’re interested in more information about types of servants, wages paid, and more, the blogpost at: https://countryhousereader.wordpress.com/2013/12/19/the-servant-hierarchy/ has some of that information and a good bibliography at the end of it. Another good article is at: http://rth.org.uk/regency-period/family-life/servants. Authors Donna Hatch and Geri Walton, among others, have done more in-depth articles on this and related topics. Thanks to my crazy week (and lack of servants), this had to be a quick one!!

Having some live-in “help” seems like such a great idea, until you begin to weigh the complications of it. I have a feeling the maids would take one look at my house and run away screaming. (or I would need a bunch of them!!)

Maybe I’m okay just muddling through on my own, thank you –unless a big enough chunk of cash comes along with the fantasy servants I’m wishing for!

Maybe I’m okay just muddling through on my own, thank you –unless a big enough chunk of cash comes along with the fantasy servants I’m wishing for!

How would you have fared in the Regency world having servants? Which ones would you still wish you could have today?

Save

Save

Save

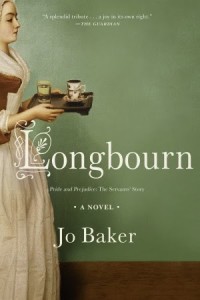

Have you read Jo Baker’s brilliant Longbourn? It’s the book that switches upstairs/downstairs in Pride & Prejudice so we get the story from the servants’ point of view. Because the servants are always there, and reading that book for me has now changed the way I read Austen.

Have you read Jo Baker’s brilliant Longbourn? It’s the book that switches upstairs/downstairs in Pride & Prejudice so we get the story from the servants’ point of view. Because the servants are always there, and reading that book for me has now changed the way I read Austen.

I’m giving a version of my talk on servants for JASNA in Minneapolis this weekend and so I’ve been sprucing up my material and  wondering whether or not to include the strange, wonderful, (slightly icky) story of Hannah Cullwick (1833-1909) and her master, Arthur Munby (1828-1910). Hannah wrote a diary, published in 1984 by Virago Press, UK (now out of print) that gives an extraordinarily detailed account of the everyday life of a Victorian servant.

wondering whether or not to include the strange, wonderful, (slightly icky) story of Hannah Cullwick (1833-1909) and her master, Arthur Munby (1828-1910). Hannah wrote a diary, published in 1984 by Virago Press, UK (now out of print) that gives an extraordinarily detailed account of the everyday life of a Victorian servant.

But it’s more than that.

Hannah wrote the diary at the instigation of her lover-employer-husband Arthur Mumby, who had a fetish for working class women and dirt, specifically women getting dirty. So a passage like this would get Arthur all hot and bothered:

Lighted the fire. Brush’d the grates. Clean’d the hall & steps & flags on my knees. Swept & dusted the rooms. Got breakfast up. Made the beds & emptied the slops. Cleaned & wash’d up…Cleaned the stairs & the pantry on my knees. Clean’d the knives & got dinner. Clean’d 3 pairs of boots. Clean’d away after dinner & began the preserving about ½ past 3 & kept on till 11, leaving off only to get the supper & have my tea…Went to bed very tired & dirty.

Boots, by the way, figure rather largely in their relationship.

Boots, by the way, figure rather largely in their relationship.

Hannah took great pride in her strength and endurance, choosing always to remain at the bottom of the Victorian servant food chain, as a maid of all work. A lawyer and amateur artist, poet, and anthropologist, Munby had a huge collection of photographs and other records of working women that he bequeathed to Trinity College Cambridge.

Hannah met Munby in 1854 and he followed her around from one position to another, watching her beat carpets and so on, and she was fired from at least one household because of his interest in her–this was a period, of course, when women servants were not allowed to have gentleman followers. Working at boarding houses rather than private houses gave her greater freedom. Eventually he hired her in 1872 and they married secretly the following year. But to all intents and purposes she was still his servant, and Munby’s friends–who included Ruskin, Rosetti, and Browning–had no idea of the true relationship, one that seems to have been classic BDSM.

For freedom & true lowliness, there’s nothing like being a maid of all work (1872)

She wore a locking chain around her neck, for which Munby had the key, and a leather strap on one wrist as a sign of his ownership. Munby posed her in various disguises–as a man, a chimney sweep, in blackface, as a fashionable lady.

She wore a locking chain around her neck, for which Munby had the key, and a leather strap on one wrist as a sign of his ownership. Munby posed her in various disguises–as a man, a chimney sweep, in blackface, as a fashionable lady.

But she had an extraordinarily strong sense of independence outside their fantasy life. She insisted, even after marriage, on receiving wages and keeping her own name, and she left him in 1877, although he continued to visit her, but presumably on her terms. You have to wonder who did wear the trousers in this relationship.

And that’s the question that seems to have plagued households, particularly during the Victorian period, when master-servant relationships seem to have escalated to an extraordinarily virulent level: who really is in charge here?

So at the moment, yes to Longbourn, and yes to Cullwick-Munby, and let’s see if anyone picks up on the subtext. And I expect they will, because smart readers of Austen always find the subtext.

I blogged a few months ago about servants and mentioned then Erddig in North Wales, one of the most-visited National Trust properties. The Yorke family, the Squires of Erddig, while not overpaying their staff were certainly fond enough of them to commission portraits or photographs of them, and write (mediocre) poetry about them.

What makes Erddig (pronounced Er-thick–it’s Welsh) unique is that all of the outbuildings, dairies, laundries, stables, dogyards etc., are intact and restored. You can see before and after photographs showing what an enormous, and daunting task this was for the National Trust, as mostof the buildings, including the house itself, were derelict. In his final months in the house the last squire camped out in the drawing room by candlelight, with bowls set out to catch the drips from the leaking roof.

The gardens and grounds are gorgeous–tulips, primroses and bluebells were in bloom, and there’s a lovely (and rare) eighteenth century walled garden. Rare historic varieties of fruit trees, espaliered against the brick walls, were also flowering.

As for the house, it’s crammed full of amazing furniture and artwork, but all very dark and oppressive. The Yorkes, a rather eccentric family, didn’t believe in throwing anything away, or unnecessary plumbing or electricity. One of the nicest rooms is the late eighteenth-century kitchen, well-lit, by tall, elegant windows, and with its original tiled floor–not much changed other than by the addition of two Victorian ranges. It was frustrating to see features of the house–like particular pieces of art–and not be able to see the details you know from photographs.

Final word: definitely worth a visit. You could spend hours exploring the gardens and grounds, and the restaurant does great food (excellent cakes and a good cup of tea). But buy a guidebook so you can really see what things should look like!