Hurrah! I finally got my hands on John Philip Kemble’s version of Shakespeare’s THE WINTER’S TALE.

Hurrah! I finally got my hands on John Philip Kemble’s version of Shakespeare’s THE WINTER’S TALE.

For those of you who don’t know — during the Regency (and for a while before), Kemble was an actor and manager at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, and later Theatre Royal Covent Garden. He valued Shakespeare highly. Under his wise yet despotic rule, London theatre saw (for the first time in a long time) Shakespeare plays that the bard himself might actually have recognized.

By contrast, the Great Garrick (the theatre despot in the early to mid 18th century), although respected for also being a restorer of Shakespeare to high repute, nonetheless produced things like “Florizel and Perdita” and “Catherine and Petruchio” — hour-long things that were part Shakespeare, part bizarre rewriting. Even better: in Garrick’s King Lear, Lear and Cordelia live, and Cordelia marries Edgar.

Kemble, though, did his best to be true to Shakespeare.

The illustration here, by the way, is Sarah Siddons playing Hermione in THE WINTER’S TALE.

The illustration here, by the way, is Sarah Siddons playing Hermione in THE WINTER’S TALE.

My favorite part of reading Kemble’s versions of Shakespeare is seeing just how prudish (or not prudish) the Regency stage was. My conclusions in the past have been that, though Regency theatregoers clearly tolerated less vulgarity than their Elizabethan ancestors, Kemble’s scripts are far closer to Shakespeare’s than to Bowdler’s.

Or, to be more precise, sex and violence are welcomed on Kemble’s stage, but indelicate expressions rather less so. (For example, the characters still talk about virginity, but don’t use such a crude word for it, instead terming it purity or honour or the like.)

(To read my earlier posts on the subject, click Regency Shakespeare or Regency AS YOU LIKE IT.)

So much for my past impressions of Kemble’s changes. Now, today’s project: let’s find some bits in THE WINTER’S TALE which Kemble changed!

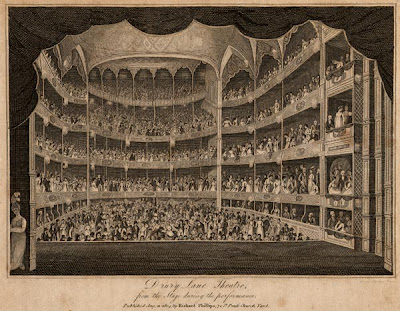

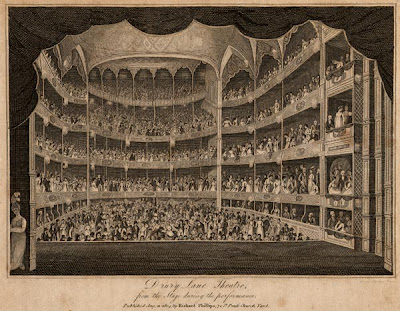

This is a picture of Drury Lane Theatre in 1804.

This is a picture of Drury Lane Theatre in 1804.

What follows is the original passage of Shakespeare’s in which King Leontes rants (half-madly) about his conviction that his wife has slept with his best friend, and is pregnant with the friend’s child. I have put in purple the portions that Kemble cut out:

There have been,

Or I am much deceiv’d, cuckolds ere now;

And many a man there is (even at this present,

Now, while I speak this) holds his wife by th’ arm,

That little thinks she has been sluiced in ‘s absence

And his pond fish’d by his next neighbour, by

Sir Smile, his neighbour; nay, there’s comfort in’t,

Whiles other men have gates, and those gates open’d,

As mine, against their will. Should all despair

That have revolted wives, the tenth of mankind

Would hang themselves. Physic for’t there’s none;

It is a bawdy planet, that will strike

Where ’tis predominant; and ’tis powerful, think it,

From east, west, north, and south; be it concluded,

No barricado for a belly. Know ‘t,

It will let in and out the enemy,

With bag and baggage: many thousand on ‘s

Have the disease, and feel ‘t not.

When the first cut above appears, Kemble has Leontes trail off (indicated by a long dash), and a hand-written stage direction reveals that another character approaches Leontes at this point (the implication perhaps being that Leontes would have finished the thought, had he not feared being overheard.)

So, that’s one example of things Kemble cut out. What are some passages, risque though they might be, that Kemble let alone? Here are a few:

You may ride us,

With one soft kiss, a thousand furlongs, ere

With spur we heat an acre.

How she holds up the neb, the bill to him!

And arms her with the boldness of a wife

To her allowing husband!

Go, play, boy, play;–thy mother plays, and I

Play too; but so disgrac’d a part, whose issue

Will hiss me to my grave;

My wife ‘s a hobby-horse; deserves a name

As rank as any flax-wench, that puts to

Before her troth-plight:

There you have it! Kemble’s alterations of Shakespeare — one of my little obsessions.

However, I have no idea if any of you are at all interested in this subject. I could happily do more posts detailing which bits of Shakespeare Kemble left in, and which he cut out — but I’ll only do so if I know it’s of interest to someone! So if you’re interested, do let me know in a comment.

And remember: our next Jane Austen bookclub meets the first Tuesday in September, to discuss the Ang Lee/Emma Thompson version of SENSE AND SENSIBILITY!

Cara

who thinks those flax-wenches got a bad rap

I’d hazard a guess that we remember these events by the two poets who immortalized them rather by the history. Here’s an excerpt from the famous St. Crispin’s Day speech by Shakespeare:

I’d hazard a guess that we remember these events by the two poets who immortalized them rather by the history. Here’s an excerpt from the famous St. Crispin’s Day speech by Shakespeare: