Every once in a while (okay, probably every month!) I order a big box of books from the Edward R. Hamilton catalog. They have wonderful remaindered and discounted research-type books, and I’ve gotten some great “finds” from them. In my last shipment, one of the books was Lisa Hilton’s Mistress Peachum’s Pleasure: The Life of Lavinia, Duchess of Bolton about the actress Lavinia Fenton who found great fame on the stage and later was the mistress (and wife) of a duke, and then as a widow lost her fortune on a much younger husband. Quelle scandale! Her big role, the one that made her an overnight sensation on the London theater scene, was as Polly Peachum in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera.

Every once in a while (okay, probably every month!) I order a big box of books from the Edward R. Hamilton catalog. They have wonderful remaindered and discounted research-type books, and I’ve gotten some great “finds” from them. In my last shipment, one of the books was Lisa Hilton’s Mistress Peachum’s Pleasure: The Life of Lavinia, Duchess of Bolton about the actress Lavinia Fenton who found great fame on the stage and later was the mistress (and wife) of a duke, and then as a widow lost her fortune on a much younger husband. Quelle scandale! Her big role, the one that made her an overnight sensation on the London theater scene, was as Polly Peachum in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera.

And today just happens to be John Gay’s birthday! Gay (June 30, 1685–December 4, 1732) was born in Barnstaple and was educated there at the local grammar school. On leaving school he was apprenticed to a silk mercer in London, but quickly grew bored with the business. But he did make a variety of influential literary friends, including Pope and Swift, who encouraged him in his writing endeavors. In 1715 he produced What d’ye call it? (1715), a dramatic satire that left the public so baffled by its meaning there was a Complete Key to what d’ye call it. He went on to produce a poem in 3 volumes, Trivia, or the Art of Walking the Streets of London and a comedic play, Three Hours After Marriage (which one critic called “grossly indecent without being amusing”–it was not a success). He made almost 1000 pounds on his Poems on Several Occasions, but lost it all in the South Sea Bubble.

And today just happens to be John Gay’s birthday! Gay (June 30, 1685–December 4, 1732) was born in Barnstaple and was educated there at the local grammar school. On leaving school he was apprenticed to a silk mercer in London, but quickly grew bored with the business. But he did make a variety of influential literary friends, including Pope and Swift, who encouraged him in his writing endeavors. In 1715 he produced What d’ye call it? (1715), a dramatic satire that left the public so baffled by its meaning there was a Complete Key to what d’ye call it. He went on to produce a poem in 3 volumes, Trivia, or the Art of Walking the Streets of London and a comedic play, Three Hours After Marriage (which one critic called “grossly indecent without being amusing”–it was not a success). He made almost 1000 pounds on his Poems on Several Occasions, but lost it all in the South Sea Bubble.

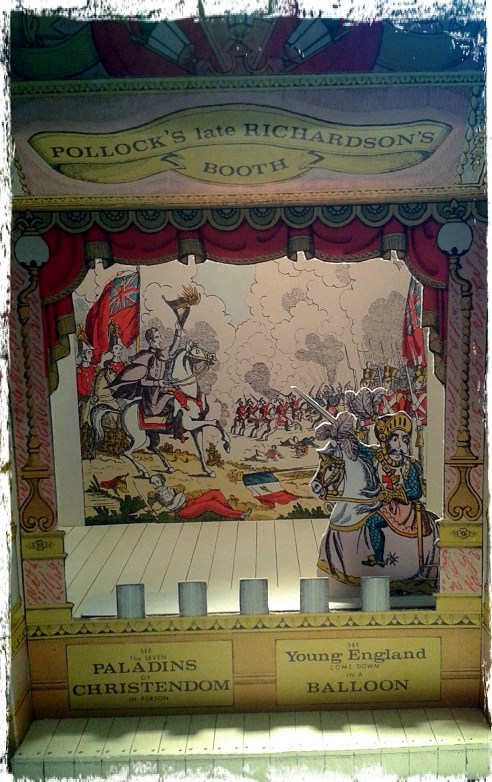

His great success came in 1728 with The Beggar’s Opera, a ballad opera in 3 acts (ballad operas were satiric musical plays that used some of the conventions of the wildly popular Italian opera, but without recitative). It had its premier at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on Janaury 28, and ran for an unprecedented 62 consecutive performances. This original production was so popular it enable John Rich, the owner of the theater, to open the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden (a popular saying of the day had it that Beggar’s Opera made “Rich gay and Gay rich”).

His great success came in 1728 with The Beggar’s Opera, a ballad opera in 3 acts (ballad operas were satiric musical plays that used some of the conventions of the wildly popular Italian opera, but without recitative). It had its premier at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on Janaury 28, and ran for an unprecedented 62 consecutive performances. This original production was so popular it enable John Rich, the owner of the theater, to open the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden (a popular saying of the day had it that Beggar’s Opera made “Rich gay and Gay rich”).

It satirized the Italian opera of the day, so popular among the upper classes, but instead of grand themes and music it used well-known tunes and characters that were ordinary (not to say criminal!) people. The audience could hum along with the music, even if they had never heard the words before. The story also satirized politics (especially statesmen like Robert Walpole), poverty and injustice, notorious highwaymen of the day, and corruption at all levels of society. It made Lavinia Fenton a big star (poems were written about her and prints of her image sold out, as well as “Polly” fans and firescreens and playing cards).

The plot goes something like this. Peachum is a fence and thief-catcher, and the opera opens with him justifying his actions. He and his wife then discover that their pretty daughter Polly has secretly married the highwayman Macheath. They’re not happy, of course, but conclude that maybe the match makes sense if the new bridegroom can be killed for his money. They leave to carry out this errand (talk about nightmare in-laws!) while Polly hides her husband in a tavern, where he is surrounded by women of dubious virtue (who like to display their perfect drawing-room manners while singing about picking pockets and shoplifting). Too late, Macheath discovers that two of the “ladies” have contracted with Peachum to capture him, and off he goes to Newgate. There the jailor’s daughter, Lucy Lockit, scolds Macheath for agreeing to marry her and then running off. She wants to torture him, but he pacifies her–until Polly arrives and declares he’s her husband. Macheath tells Lucy Polly is just crazy, and Lucy helps him escape. Lucy’s father is none too happy about this, either, and joins forces with Peachum to find Macheath and split up his fortune between them.

Lucy tries to poison Polly, but then they too join forces to save Macheath when he is recaptured. Then four more women show up, claiming to be his wives (his pregnant wives!). Macheath decides he’s ready to be hanged. The narrator (the Beggar) says that in a properly moral tale he would be hanged, but the audience demands a happy ending, so Macheath is reprieved and all are invited to a dance to celebrate his wedding to Polly.

Gay tried to follow up this smash hit with a sequel, Polly, where Macheath has become a pirate and Polly has to escape from white-slavers. But Walpole had had enough of this satire, and leaned on the Lord Chamberlain to have it banned (it was first performed 50 years later). John Gay was buried in Westminster Abbey with an epitaph on his tomb by Pope, along with his own concluding couplet: “Life is a jest, and all things show it, I thought so once, and now I know it.”

Gay tried to follow up this smash hit with a sequel, Polly, where Macheath has become a pirate and Polly has to escape from white-slavers. But Walpole had had enough of this satire, and leaned on the Lord Chamberlain to have it banned (it was first performed 50 years later). John Gay was buried in Westminster Abbey with an epitaph on his tomb by Pope, along with his own concluding couplet: “Life is a jest, and all things show it, I thought so once, and now I know it.”

Have you ever seen a production of Beggar’s Opera you really enjoyed? Or have any ideas for a book set among characters like this? (We don’t see them too often in romances, of course; our characters would be more likely to be the ones satirized! But I’m working on research for an Elizabethan story set among similar theatrical people, and having lots of fun with it…)

And, on a totally unrelated note, I’ve posted some new author photos for Laurel McKee on my own blog! I can’t decide which I like best. What do you think???

And, on a totally unrelated note, I’ve posted some new author photos for Laurel McKee on my own blog! I can’t decide which I like best. What do you think???