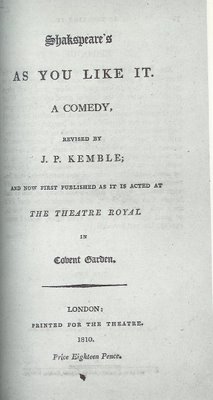

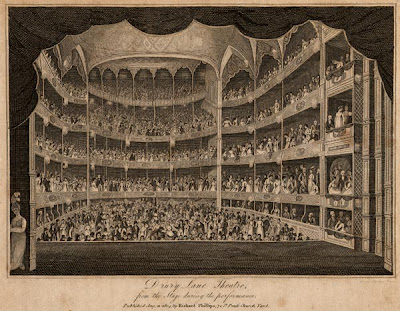

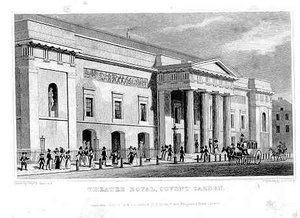

As I mentioned in last Tuesday’s post, I’m currently in a production of Shakespeare’s AS YOU LIKE IT. Which, of course, makes this the perfect time for me to go over John Philip Kemble’s version of the play — which was the version used at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden during the Regency, and was also published and sold (for eighteen pence a copy).

As I mentioned in last Tuesday’s post, I’m currently in a production of Shakespeare’s AS YOU LIKE IT. Which, of course, makes this the perfect time for me to go over John Philip Kemble’s version of the play — which was the version used at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden during the Regency, and was also published and sold (for eighteen pence a copy).

So, what changes did the great actor/manager/director (pictured here) make to Shakespeare’s text?

I was delighted to find that the answer is, very few!

Let’s start with what Kemble left in. The following are words and phrases that Kemble clearly thought acceptable for general audiences to hear and read: damn’d, damnation, bastard, foul, slut, puking, belly, stomach, body, bawdry, udders, country copulatives, virgin, maid

The most vulgar speech that I could find that he left in was said by Touchstone the Fool, who is pretending to scold a shepherd for the immorality of his profession:

That is another simple sin in you: to bring the ewes and the rams together, and to offer to get your living by the copulation of cattle: to be bawd to a bell-wether; and to betray a she-lamb of a twelvemonth, to a crooked-pated, old, cuckoldy ram, out of all reasonable match. If thou be’st not damn’d for this, the devil himself will have no shepherds…

Some of the cuts (most of them quite short — a line here or there) were, as far as I can tell, just for length, or occasionally to cut an obscure passage. Some, though, were probably for the indelicacy of the topic, or the vulgarity of the phrasing — but even this seems not to be invariable. Touchstone talks a fair amount about horns (a constant joke in Shakespeare’s plays, where all men seem to eternally fear being cuckolded), but a couple lines of Rosalind’s joking about horns was cut. Perhaps in this case, the jokes themselves were not too warm, but the character of Rosalind was now thought to be too refined to make such jokes?

And yet Rosalind did keep some of her suggestive lines. Kemble left in the passage which reads:

ROSALIND: … till you met your wife’s wit going to your neighbor’s bed.

ORLANDO: And what wit could wit have to excuse that?

ROSALIND: Marry, to say,–she came to seek you there.

On the other hand, Kemble cut the passage:

ROSALIND: I prithee take the cork out of thy mouth, that I may drink thy tidings.

CELIA: So you may put a man in your belly?

Other passages that were presumably cut for indelicacy include:

CELIA: You will cry in time, in despite of a fall. (This is a double joke, referring to both sex and childbirth)

TOUCHSTONE: He that sweetest rose will find, must find love’s prick and Rosalind.

Also cut was a longish passage in which Touchstone and the shepherd compare a shepherd’s greasy hands (due to handling ewes’ “fells”) and a courtier’s hands, perfumed with civet (“the very uncleanly flux of a cat.”)

Kemble invariably cut “God” (e.g. “I thank God” and “God save you”) and changed it to “heaven” (so: “I thank heaven” and “Heaven save you”) — so I presume this was consistently done on the Regency stage.

Well, that’s AS YOU LIKE IT as Kemble liked it! Hope you liked it too…

Cara

Cara King, www.caraking.com

MY LADY GAMESTER — out now from Signet Regency!