My creative work has currently been interrupted – most pleasantly so, I might add! – by my academic work: I have been invited to contribute an essay about a background topic (“Themes of Medievalism in Punch“) to Cengage’s new digital Punch Historical Archive. For this I have also been given access to the archive itself, and it’s – oh my gosh! – fantastic! Not only can you do full text searches across all volumes of Punch from 1841 to 1992, but to make this even better, the large cuts (= the big political cartoons) and the social cuts (=smaller cartoons) have also been indexed. *swoons*

But it gets even better: one of my friends from Liverpool John Moores University, Clare Horrocks, is transcribing the contributors’ ledgers of Punch, and her findings will be incorporated into the archive. This is really important work because for much of the nineteenth century, writing for periodicals was done either anonymously or pseudonymously. So, as was pointed out in an article in a recent issue of American Libraries, Clare’s work helps us to solve questions of authorship and attribution:

Early findings from the project have revealed articles written by William Makepeace Thackeray and P. G. Wodehouse that were previously unattributed. And while Charles Dickens himself never wrote for the magazine, his son Charles Dickens Jr. is known to have contributed a number of articles, which this project expects to uncover.

Yet as awesome as the digital archive is, in certain points it cannot replace leafing through the actual volumes: smaller illustrations like initial letters have not been indexed (and I would imagine that this would actually be a rather impossible task given the vast numbers of itty-bitty illustrations in Punch). Moreover, leafing through volumes and looking at images can reveal certain themes that you would not notice otherwise.

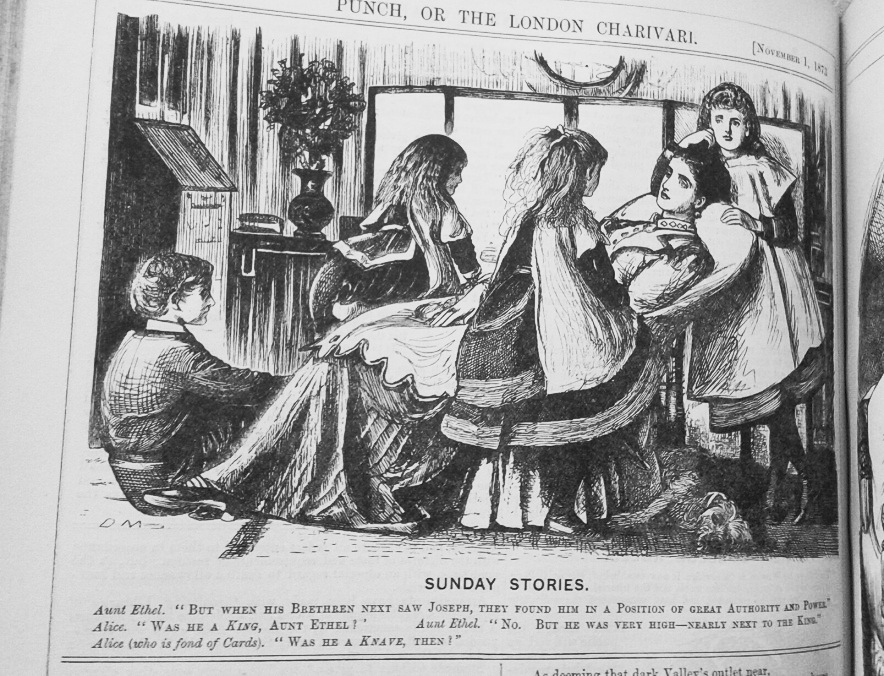

I found this out when I checked initial letters in different volumes from the 1850s, 60s, and 70s (in search for medieval themes, of course!) (or rather, I wanted to pinpoint when medieval themes vanished from the initial letters). And while I was leafing through the 1873 volume, looking for itty-bitty knights, I suddenly noticed an abundance of pet dogs in the social cuts.

Now, it’s not as if dogs hadn’t appeared before 1873: Mr. Punch himself, after all, is accompanied by his dog Toby; in the 1840s Richard Doyle fell into the habit of adding little Toby-ish doggies to many of his drawings; and in social cuts dealing with country sports you can often find hunting dogs. But the many, many pet dogs of 1873 is not something that you see in the 1840s. Clearly, some of the artists who worked for Punch in the 1870s must have been dog lovers.

Like George du Maurier:

(Or perhaps, he just wanted to poke fun at bourgeois ladies and their pet dogs.)

(Or perhaps, he just wanted to poke fun at bourgeois ladies and their pet dogs.)

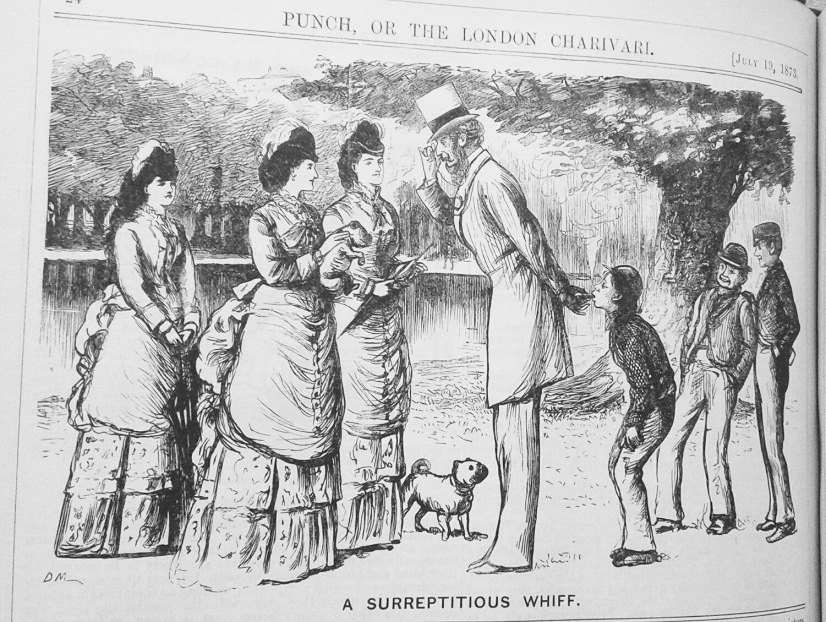

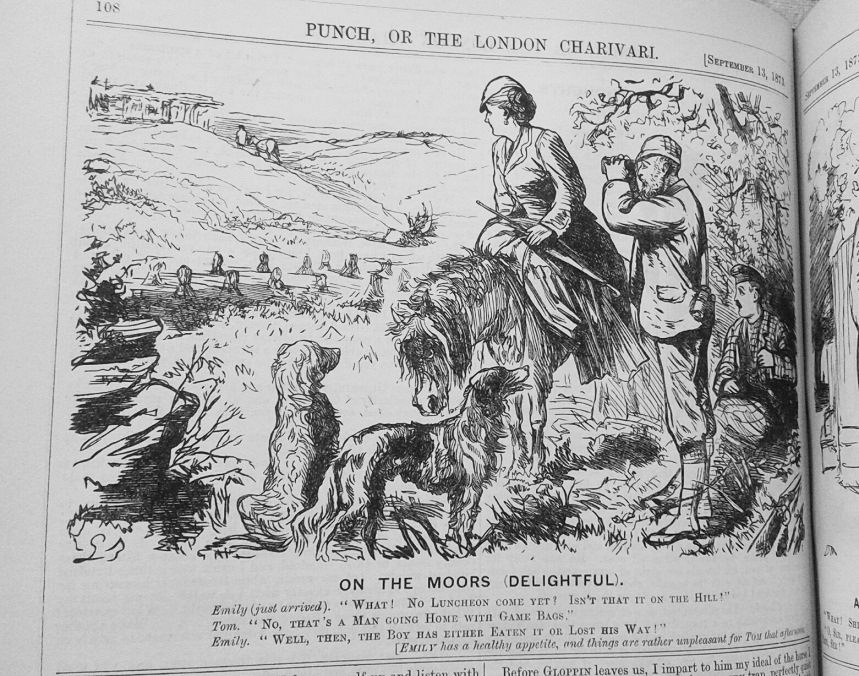

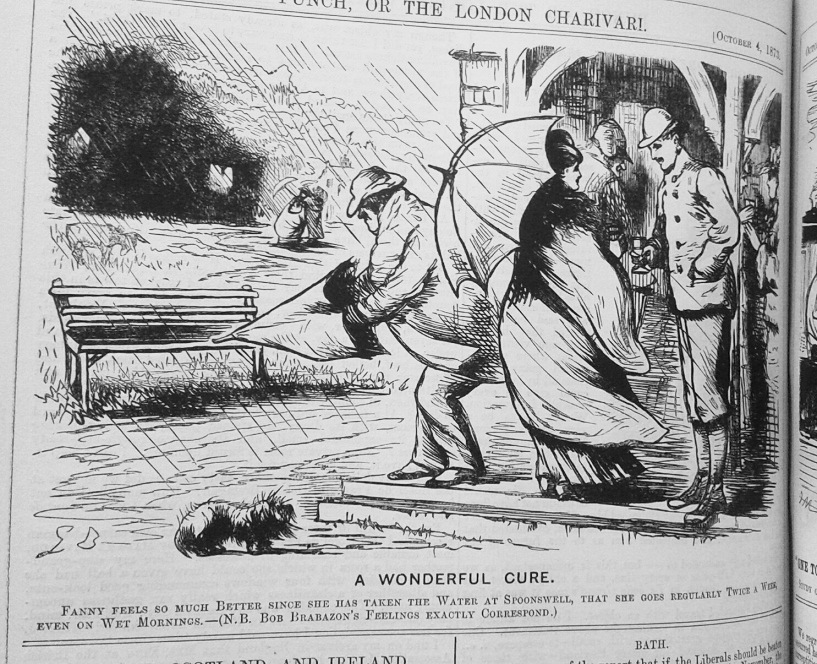

And then, there is GB, whose dogs are truly delightful:

And do you know what else is truly delightful about GB? GB is a woman!!! The initials stand for Georgina Bowers. In his History of Punch (1895) Spielmann calls her “[b]y far the most important lady artist who ever worked for Punch […],” and continues,

Miss Bowers was a humorist, with very clear and happy notions as to what fun should be, and how it should be transferred to a picture. Her long career began in 1866, and thenceforward, working with undiminished energy, she executed hundreds of initials and vignettes as well as “socials,” devoting herself in chief part to hunting and flirting subjects.

Of course, being a woman, she had to be shown the proper way of doing illustrations for the magazine *snort*: “It was John Leech [Punch‘s chief artist] who set her on the track; Mark Lemon [Punch‘s first editor], to whom she took her drawings, encouraged her, and with help from Mr. Swain [the engraver] she progressed.” (Oh, Mr. Spielmann! *shakes head sadly*)

Georgina worked for the magazine for ten years until differences with a new editor made her resign. But she seems to have continued to work as an illustrator for many more years.

Isn’t that a lovely find?