At this moment we are all affected by the Coronavirus pandemic. I, for one, am rather obsessively following all the news about it. I hope everyone is practicing social distancing and staying home, washing hands, and any other measures necessary to keep from spreading the disease.

We all are quarantined, to some degree or another. I hope none of you or your loved ones have contracted the disease. These are scary times.

“Our” era, (Regency England in the early 19th century) was no stranger to feared outbreaks of contagious illness. Smallpox, the Speckled Monster, was one of the most deadly. In 18th century England, smallpox was responsible for half of the deaths of children under age 11.

Smallpox is a viral disease characterized by fever, vomiting, and a skin rash covering the body with fluid-filled bumps which scab over and often cause severe scarring, blindness or death.

Smallpox was present in ancient times, as early as 360 BC in China. It is thought that Ramses V, Pharaoh of Egypt, died of small pox in the 12th century BC. By the 1700s the disease had been spread to the New World, decimating the indigenous populations of North and South America and Australia.

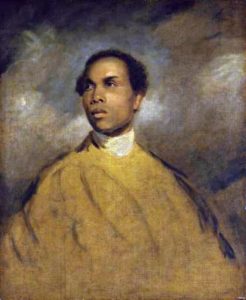

There were no effective treatments for smallpox in the Regency era, although, in 1767, William Watson, a physician at the Foundling Hospital in London tried unsuccessfully to treat it with mercury and laxatives. What was effective was preventative inoculation. Inoculation, pricking the skin with the fluid from a smallpox pustule, had been practiced for a long time in China, India, parts of the Middle East, the Ottoman Empire, parts of Africa, and even in Wales, but it did not become widely used in the West until the 1700s. One of its proponents had been Lady Mary Montagu, wife of the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, who had learned of the practice when in Turkey. Her brother had died of smallpox and she herself had suffered the disease. She had her own children inoculated.

Inoculation was not without its risks. While most patients experienced mild symptoms, some patients developed the full disease and died. It did, however, greatly reduce the death rate from smallpox.

In 1796 Edward Jenner created a vaccine for smallpox from the much milder disease of cowpox. It had been observed by Jenner and his colleagues that people who had suffered cowpox did not contract smallpox. Jenner’s vaccination was much safer than inoculation with the smallpox virus itself.

Certainly, the push for vaccination for smallpox would have taken place in the Regency Era and our characters would have known of it and likely would have taken the vaccine. It took awhile for inoculation and vaccination to be universal, but wide vaccination effectively erraticated the disease by 1977.

How are you all coping with our pandemic?